Marketing failure stories spread faster than wildfire. We’ve all heard them: Pepsi accidentally promising to resurrect the dead in China, Chevrolet Nova flopping because “no va” means “doesn’t go” in Spanish, KFC telling customers to “eat your fingers off.”

These tales get shared at marketing conferences, repeated in business schools, and cited in countless articles about the importance of cultural awareness. There’s just one problem: most of them never actually happened.

The legends that won’t die

The Chevrolet Nova story is perhaps the most persistent marketing myth. The tale goes that General Motors struggled to sell the Nova in Latin America because “no va” means “it doesn’t go” in Spanish. It’s a compelling cautionary tale about translation failures.

Except it’s false. The Nova sold well in Spanish-speaking countries. As Snopes and multiple automotive historians have documented, Spanish speakers don’t mentally break down “Nova” into “no va” any more than English speakers think “notable” means “no table.”

The KFC “finger-lickin’ good” translation disaster follows a similar pattern. According to the widespread story, KFC’s famous slogan translates to “eat your fingers off” when the chain expanded to China. Like the other legends, this tale serves as a perfect cautionary example about the perils of literal translation. However, there’s no documented evidence that this translation error ever occurred. KFC has been operating in China since 1987, and while they’ve certainly faced various challenges in international markets, this particular translation mishap appears to be another marketing myth that sounds plausible enough to keep circulating.

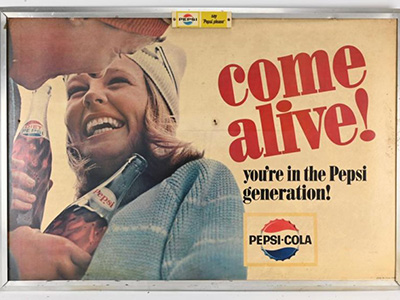

The Pepsi translation disaster is equally fictional. No evidence exists that Pepsi’s “Come Alive with Pepsi” ever translated to anything about ancestors or the dead. Yet this story appears in marketing textbooks and continues to be shared as fact.

Why do these false stories persist? Because they reinforce our fears about international marketing while providing simple, memorable lessons. They’re too useful to fact-check.

Why we love marketing disaster stories

These myths reveal something important about how we think about communication. We’re simultaneously fascinated by and terrified of the ways language can betray us. The stories persist because they:

- Simplify complex cultural differences into easy-to-understand warnings

- Make us feel smart for knowing about potential pitfalls

- Provide justification for hiring expensive consultants and translation services

- Turn abstract concepts like ‘cultural sensitivity’ into concrete examples

The problem is that when we repeat false stories, we’re not actually learning how to communicate better. We’re just spreading misinformation.

Real examples of marketing gone wrong

While the classics are often fake, plenty of genuine marketing mishaps have happened. The difference is that real failures are usually more complex and less dramatically satisfying than the legends.

Social media disasters:

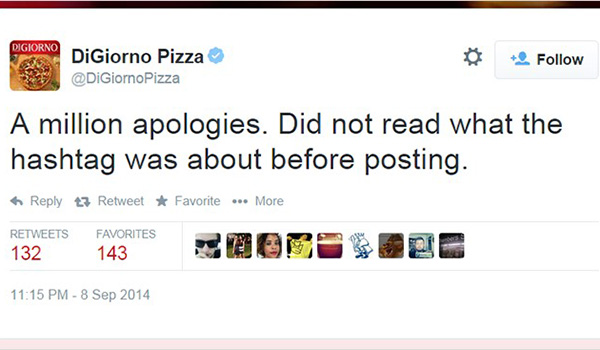

- DiGiorno Pizza #WhyIStayed incident (September 2014)

Twitter lit up after the suspension of NFL player Ray Rice for beating his wife, Janay, with thousands of women opening up about #WhyIStayed in violent relationships. Janay Rice has faced criticism for her decision to stay with her husband following the incident of domestic abuse. But in an attempt to stay #social #media #relevant, DiGiorno’s Twitter account hijacked the trending hashtag to… sell frozen pizza.

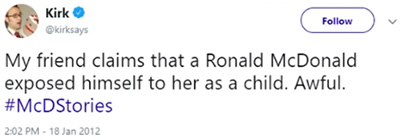

- McDonald’s #McDStories campaign (2012)

McDonald’s launched a Twitter campaign using the hashtag #McDStories; it was hoping that the hashtag would inspire heart-warming stories about Happy Meals. Instead, it attracted snarky tweeps and McDonald’s detractors who turned it into a #bashtag to share their #McDHorrorStories.

Product naming issues:

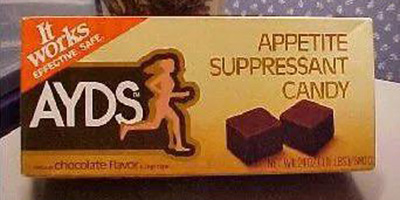

- Ayds diet candy

Ayds Diet Candy’s success was undeniable during the 1970s. However, it was during the 1980s that a perfect storm of circumstances began to brew, eventually leading to its downfall. The name ‘Ayds,’ which had been innocuous in the 1960s, took on a sinister connotation as the AIDS epidemic emerged.

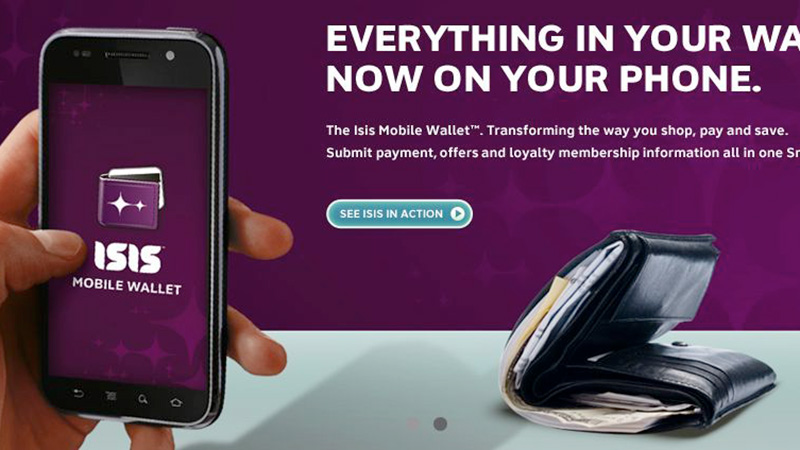

- ISIS mobile payment system

The Isis mobile wallet app is ditching its name to avoid confusion with the Islamic militant group that released videos showing the executions of two American journalists. The app, which allows users to tap their smartphones to pay for goods, will rebrand itself as Softcard, Isis Chief Executive Michael Abbott said Wednesday.

- New Zealand band Shihad

Shihad changed their name to Pacifier in 2002 due to the similarity of their name to the word ‘jihad’ following the 9/11 terrorist attacks. The name change was a failed attempt to break into the American market, and after a backlash from their fans at home, the band reverted to their original name, Shihad, in 2004.

Digital blunders:

- Kendall Jenner Pepsi ad

The soda brand has run into controversy with its recently pulled two-and-a-half-minute ad in which model Kendall Jenner joins a protest and seems to defuse tensions with police officers by handing one a can of soda.

- Dove’s advertising campaign

Dove’s 2017 Facebook ad showed a sequence of three women removing shirts: a Black woman revealing a white woman underneath, followed by the white woman revealing an Asian woman. The imagery was widely interpreted as suggesting that using Dove soap could transform Black skin to white, echoing harmful historical advertising tropes about skin lightening. Despite Dove’s claims that the ad was intended to show diversity and that longer versions provided more context, the brand quickly pulled the campaign and apologised. The incident became a textbook example of how visual messaging can communicate unintended meanings regardless of stated intentions

Not reading the room:

- American Eagle – Sydney Sweeney controversy

American Eagle’s “Sydney Sweeney Has Great Jeans” campaign launched in July 2025, featuring the Euphoria star in denim advertising. The campaign played on the sound similarity between “genes” and “jeans,” with taglines referencing both her physical attributes and the clothing. Critics argued the wordplay reduced Sweeney to her physical appearance and perpetuated objectification, while supporters dismissed the backlash as manufactured outrage. The controversy highlighted how brands can misjudge public sentiment around messaging that walks the line between clever wordplay and inappropriate commentary.

- e.l.f. Cosmetics under fire for Matt Rife ad

The budget beauty brand partnered with comedian Matt Rife for an August 2025 campaign featuring him alongside drag queen Heidi N Closet in lawyer roles. The backlash centred on Rife’s previous controversial comments, particularly a domestic violence joke from his Netflix special that had already drawn criticism from female audiences. Many questioned why e.l.f., a brand popular with young women, would partner with someone who had made light of domestic abuse. The incident demonstrated how past controversies can derail current marketing efforts when brands fail to thoroughly vet their celebrity partners.

Today’s marketing failures are often more subtle but no less damaging. They include:

- Brands jumping on social media trends without understanding their context

- Automated systems generating inappropriate ad placements

- AI-generated content that misses cultural nuances

- Influencer partnerships that backfire due to poor vetting

These modern mishaps are usually documented with screenshots, news coverage, and corporate apologies, making them much easier to verify than the vintage legends.

What we can learn

The persistence of false marketing stories teaches us something valuable: we prefer simple explanations to complex realities. A translation error that creates an embarrassing double entendre is easier to understand than the subtle cultural factors that determine whether a product succeeds in a new market.

Real marketing failures are usually the result of multiple factors: poor research, insufficient cultural understanding, bad timing, or simple human error. They rarely come down to a single word choice or translation mistake.

And why a picture of a dog? Just to see if you’re really reading this. And because I like dogs.

The next time someone shares a marketing disaster story that seems too perfect, too funny, or too neatly illustrative, take a moment to question it. The most educational failures are often the verified ones, even if they’re less dramatic than the legends.

Real marketing mishaps teach us about the complexity of human communication, the importance of context, and the value of testing and research. The fake stories just teach us to repeat urban legends.

Where misinformation spreads easily, marketing professionals have a responsibility to share accurate examples, not perpetuate myths. The truth is usually more complex but ultimately more useful than fiction.